You’ve probably snapped a picture in the last few days, right? With cameras in our phones, in our tablets, on the front of our computers and… well, in actual dedicated cameras, we’ve taken more pictures in the last ten years than in the previous hundred years put together. You might be curious as to when we started taking pictures. Read on to find out.

You’ve probably snapped a picture in the last few days, right? With cameras in our phones, in our tablets, on the front of our computers and… well, in actual dedicated cameras, we’ve taken more pictures in the last ten years than in the previous hundred years put together. You might be curious as to when we started taking pictures. Read on to find out.

The history of the camera dates back nearly 2500 years; philosophers like Mo Ti and Aristotle experimented with light—that’s actually the root of the word “photography.” It’s derived from the greek words photo meaning “light” and graphos meaning “to write.” From 500BC to the 19th century there were evolutions in the science of capturing light and refining how that light looked by focusing it through a lens.

But really, if we’re getting down to the modern idea of the camera, we need to turn to George Eastman in 1885.

Eastman’s Photographic Film

Prior to George Eastman’s introduction of Photographic Film, photographers had used metal or glass plates that were coated in a photo sensitive material. These plates were inserted into a camera, and exposed to light by removing the camera’s lens cap for a period of time. That’s why you don’t see anyone smiling in “old timey” photographs; it’s not that they weren’t happy (though living in an era when you could die at 40 from gum disease probably wasn’t delightful), it’s because holding a smile for any extended period of time was difficult, and led to blurry pictures. Instead, photographic subjects would strike a pose and stay as still as possible for between seconds and minutes. As these plates were made more sensitive, camera manufacturers began using mechanical shutters that were triggered by a button or shutter release. These allowed shorter, more accurately timed exposures to be made; consequently people in pictures started to look happier.

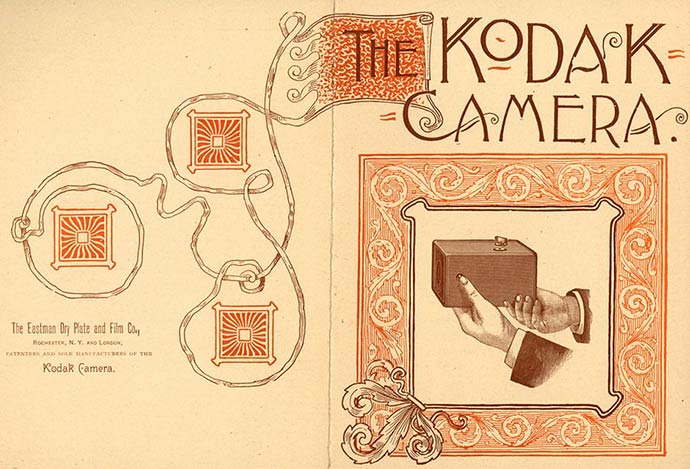

(Kodak brochure: from oldbike.eu)

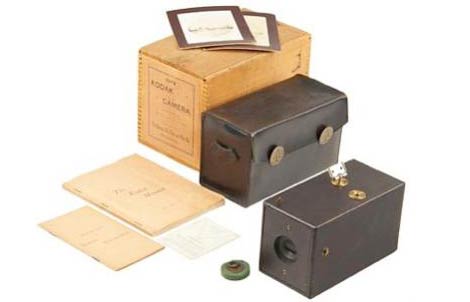

Back to George Eastman; in 1885 the Eastman Corp started to sell paper film that was more flexible and easier to use than metal plates. Three years later, Eastman released a simple, fixed-focus box camera with a single shutter speed. Like the Canon Digital Elph and the Digital Rebel after it, the “Kodak” was loved by many for its ease of use and its relatively low cost. This “Kodak” camera came with enough film to take 100 pictures; the entire camera was sent back to the Eastman Corp for processing and reloading.

Over the next 100 years we saw the continued evolution in camera technology: “film” was designed to be replaceable, coming in rolls that ordinary consumers could change on their own. Lenses were refined to offer better clarity and colour, eliminating chromatic aberration, while offering a mix of focal lengths.

Digital Revolution

The biggest change came in 1975 when an engineer from George Eastman’s company now renamed “Kodak” developed a digital camera from a charge-coupled device that recorded digital images to magnetic tape at a whopping 0.01 megapixels. That signalled the beginning of the end for film. Digitally photogrphy improved incrementally over the now 40 years since it began. If you’ve pulled out your camera recently you have probably shot upwards of 8.0 megapixels, with a lens that may or may not zoom up to 12x (on average).

Every piece of camera technology for the past 2500 years has brought us closer to this point, and future evolutions are still changing how we see digital imaging. 3D Stereoscopic digital pictures and video are possible, even with only one lens, and companies like Lytro introducing cameras that can change focus and depth of field after the picture is taken. One thing is certain: digital cameras are cool, and they’re not slowing down!

Top image:

“One Kodak Camera” by Kodakcollector – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File![]() ne_Kodak_Camera.jpg#/media/File

ne_Kodak_Camera.jpg#/media/File![]() ne_Kodak_Camera.jpg

ne_Kodak_Camera.jpg