While we often talk about the megapixel count of various cameras, we rarely talk about the size of the sensor that holds those pixels. And yet sensor size is the most important factor when it comes to image quality.

Today I’m going to delve into the nuances of sensor size and explain why it’s always worth paying attention to.

Sensor size and the crop factor

Crop factor is an important concept to understand when it comes to sensor size and lens choice, so let’s take a look at a specific use case where it comes into play—portrait photography. For the most part, when we make a portrait we want to flatter our subject, but not all focal lengths are equally flattering to the human form. Shorter focal lengths (or wide angles) provide wider views which make people look, well, wider. The general preference of photographers is to shoot portraits at a focal length of 80mm or above, because there’s less unflattering distortion. In fact an 85mm prime lens is considered the ideal portrait lens. But because of crop factor, ‘85mm’ isn’t always 85mm. And sometimes 50mm is 80mm. Confused? Well read on and we’ll try to clear these muddy waters.

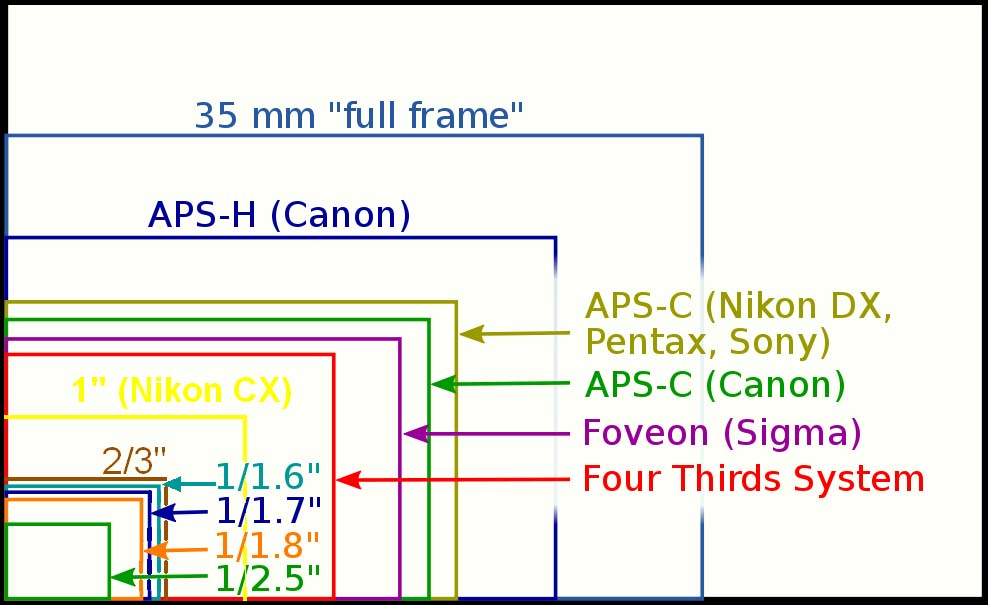

Different cameras have different sensor sizes

Crop factor arises essentially because we have such a variety of camera types in this digital age, and they carry sensors of various dimensions. In the good old days of film the majority of cameras shot 35mm film, so that was the standard, and you didn’t need to worry about the interplay between film size and focal length, you just learned what focal lengths worked for different types of photography and away you went.

The equivalent of the old 35mm film stock is referred to in the digital world as ‘full-frame’ and a full frame sensor is the same size as an old 35mm negative. The reason for this equivalence is so that you can use old lenses on new cameras, and get the same results (at least in terms of angle of view).

Don’t confuse film size with focal length

Before I go any further I want to address a possible area of confusion. In any discussion of crop factor, you’re going to see reference to “35mm”, because as I said before, this was the standard film size that many lenses were designed to work with. This 35mm refers to the width of the film, and has nothing to do with focal length. It’s just a coincidence that 35mm is also a popular focal length for lenses.

Fixed lens cameras use equivalent focal lengths

If you shoot with a fixed lens camera, like the Sony RX10, crop factor should not be an issue for you because manufacturers program these cameras to do the math for you, and only show you the 35mm equivalent focal lengths. But if you’re working with an interchangeable lens camera, you’ll probably have to figure it out for yourself.

Lenses make circular images, not rectangular

You’ve probably never thought about the fact that while every lens is circular, the images we get from our cameras are always rectangular. And indeed, the image thrown by your lens is in fact circular. You can prove this simply by pointing a lens (detached from the camera body) out a window and holding a piece of paper close to the back. When you get the distance right you’ll see a circular image of the scene outside. You really should try this—it’s very cool. It’s also interesting to notice that the image is upside down.

Rectangular sensors make rectangular images

The reason our photos are rectangular is because our sensors, the light sensitive component that actually captures the image, is also rectangular. Of course the rectangle is a much easier shape to work with in manufacturing terms, which is why we see our images on rectangular screens, and in rectangular frames, and in rectangular books. But it’s important to bear in mind that our sensors are capturing just some of the scene that the lens is seeing, not all of it.

If you’re working with a full frame sensor you’re getting the biggest image you can get from that lens, if you’re working with a camera that has a smaller sensor you’re getting less.

The difference between a full-frame and a cropped sensor

Let’s say you take a photo with a full frame camera, like the Nikon D610, and a 50mm lens, and then take the same photo with a camera with a smaller sensor (but the same lens), like the Nikon D3300, and then make an 8×12 print with each image, the image from the D3300 will appear more ‘zoomed-in’. In fact, to get the same image from the full frame sensor, you would need a shoot at a focal length of 75mm.

How did I get to 75mm? I multiplied by 1.5, which is the crop factor of the smaller sensor in the Nikon D3300. So a 50mm lens on a D3300 acts like a 75mm lens on a full frame.

Canon’s cropped sensor is referred to as APS-C, and this size is also used by Fujifilm’s X-Series. The crop factor for this size of sensor is 1.6, so a 50mm acts like a 80mm, which is a perfect focal length for portraits.

Olympus’ mirrorless cameras use the Micro Four Thirds sized sensor, for which the crop factor is 2. So a 50mm lens on an OM-D E-M10, for example, acts like a 100mm.

If you want to know the crop factor for your camera, look in the specifications where you might see it listed as the ‘focal length conversion factor’.

Buy the biggest sensor you can afford

While it might seem that using a camera with a smaller sensor gives you a bonus zoom, you should always remember that bigger is better when it comes to sensors. Bigger sensors capture more of the scene, which gives you more to work with later. You can always crop your final image tighter if you wish; you can never get back parts of the scene that were outside your frame. Also, bigger sensors have better low-light performance, which is a nice advantage. The rule of thumb when buying a new digital camera should always be: buy the biggest sensor you can afford.

I hope that helps you understand the interplay between sensor size and lens choice, but if you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below.