Let’s start at the very beginning …

A time before time

Nowadays, we schedule everything right down to the very minute. Your job interview? That’s at 10:30—not 10:25, and definitely not 10:40. The kids’ first day at school? You’re going to need to get them there right for 8:15; 8:20 is too late.

But what about a time without time? When you have a civilization without clocks, there’s no “I’ll see you at seven;” you have to operate more in terms of “we shall meet once again at the sunrise three moons from today, friend Coul!”

The first sundials were created somewhere around 2000-1500 BCE, and that’s where our story begins.

1200-1400s: Here come the clocks

Sundials worked for a while (well, a few thousand years worth of “a while”) but they’re not the most reliable way to tell time. For starters, you can’t move a sundial—you set it up, you hope it’s right, and you come back to it whenever you need to know what time it is. But beyond that, if there’s no sun, there’s no shadow, and you just aren’t able to read the time until the sun comes back!

Here in Canada, that would mean that every night past 5pm in the winter would be timeless, and every cloudy day (even if there’s a string of ten consecutive cloudy days) would exist in a sort of listless fugue. So in the late 1200s, when the first mechanical clock was invented in England, the tides really started to change.

1500s-2000s: The wristwatch makes its first appearance

From the 1200s to the 1500s, the world operated on time, but not personal time. Personal timepieces first started popping up around the 16th century, in either 1574 or 1571, depending on who you ask. Some say that the first pocket watch was created in 1574, crafted from bronze, but others say that the first wristwatch sprang to life in 1571, when a man by the name of Robert Dudley gifted an “arm watch” to Elizabeth I. (The first watch made specifically for the wrist didn’t appear until 1812, but it, too, was a gift—this time for Caroline Murat, the Queen of Naples.)

Either way, the personal timepiece started taking off in the late 16th century, in the form of pocket watches for men (who carried them almost exclusively right up until the 20th century) and pendants or wristwatches for women.

» Why pocket watches? The personal timepiece moved from men’s necks to their waists around the 17th century when Charles II of England introduced waistcoats. They took the fashion world by storm, and offered a handy place to carry one’s timepiece!

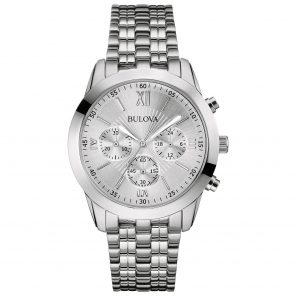

Moving later into the 1600s, we see the addition of minute (1680) and second (1690) hands to clocks. Then, jumping forward by 200-odd years, the first stopwatch springs to life! Patented by Nicolas Rieussec in 1822, the “seconds chronograph” was made to act as a timekeeper to measure distance travelled, and is still seen echoed today in products like Bulova’s Classic Dress Watch which tracks your time with much the same results. (Minus the analog setup and wild inaccuracies, of course.)

Moving later into the 1600s, we see the addition of minute (1680) and second (1690) hands to clocks. Then, jumping forward by 200-odd years, the first stopwatch springs to life! Patented by Nicolas Rieussec in 1822, the “seconds chronograph” was made to act as a timekeeper to measure distance travelled, and is still seen echoed today in products like Bulova’s Classic Dress Watch which tracks your time with much the same results. (Minus the analog setup and wild inaccuracies, of course.)

This story begins to come to a close in 1914, when watches first make their way onto the wrists of men—this time as a method of synchronizing time for soldiers at the end of World War I. Not long after, in 1954, the first successful electric watch is made by the Hamilton Watch Company, and through the 60s, Seiko begins to introduce a range of incredibly accurate quartz-crystal timepieces and wristwatches. They’re brought into the mass market in 1983, when the brand releases the first plastic Swiss quartz watch—an affordable pairing that still persists in today’s activewear market, in functional pieces like the Lorus Analog sport watch

This story begins to come to a close in 1914, when watches first make their way onto the wrists of men—this time as a method of synchronizing time for soldiers at the end of World War I. Not long after, in 1954, the first successful electric watch is made by the Hamilton Watch Company, and through the 60s, Seiko begins to introduce a range of incredibly accurate quartz-crystal timepieces and wristwatches. They’re brought into the mass market in 1983, when the brand releases the first plastic Swiss quartz watch—an affordable pairing that still persists in today’s activewear market, in functional pieces like the Lorus Analog sport watch

But why does my watch read IIII?

See this Seiko watch on the right … four bars or IIII is shown as the number 4. Why? Well, that’s a great question—and one that there might not be a great answer for. If you’ve noticed that the Roman numerals on your watch face represent 4 with a IIII instead of (the correct) IV, it’s probably actually just an aesthetics thing! In order to keep the watch face visually balanced, many watchmakers opt for a “heavy” IIII to balance with the VIII at 8 o’clock.

See this Seiko watch on the right … four bars or IIII is shown as the number 4. Why? Well, that’s a great question—and one that there might not be a great answer for. If you’ve noticed that the Roman numerals on your watch face represent 4 with a IIII instead of (the correct) IV, it’s probably actually just an aesthetics thing! In order to keep the watch face visually balanced, many watchmakers opt for a “heavy” IIII to balance with the VIII at 8 o’clock.

It’s the same reason as to why watches are usually photographed with the time reading 10:09 or 10:10—they’re just prettier that way.

The Smartwatch: 2000s and beyond

So, what about today? Watches are no longer a necessity with computers and smartphones left and right, so the industry has adapted to stay current. The classic analog watch is holding strong as a fashion statement, but the cutting edge of technology in personal timepieces right now isn’t quartz-crystal or batteries—it’s smartwatches.

Today, you can get watches that track your running speed and cadence. You can get watches that connect to your phone via Bluetooth and come with in-built GPS. You can get watches that will give you everything from social media notifications to traffic updates, all while defaulting to a classic (fake-)analog watch face, as in the super-slick Motorola Moto 360 Smartwatch.

You can even, in the case of the infamous Pebble Smartwatch, find a watch that won’t just display your text messages, but will allow you to communicate with your house.

How cool is that? Being able to talk to your house with the little dongle on your wrist. I bet the people who built Stonehenge couldn’t have seen that one coming in four thousand years.